The Debate Over Export Controls on Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment to China

Measure twice, cut once

BLUF: Export controls on semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME) should only be applied on select equipment, against select firms, and in coordination with relevant allies. Broad export controls on categories of equipment, targeting an indiscriminate number of end users/end uses, and without allies, will hurt the US SME industry more than it hurts the target.

In plain English, this means export controls should only be applied to advanced SME sales to China, against specific firms like SMIC, in coordination with The Netherlands and Japan. The goal of these policies should be to keep the Chinese semiconductor industry around two generations (2-4 years) behind the industry’s leading edge.

Introduction

The US government has imposed export controls on sales of semiconductor technologies to China for a long time. Lately there have been particular concerns about selling advanced SME to China given the dual use (civilian and military) applications of the chips this equipment makes, especially because China is clearly willing to lie, cheat, and steal its way to get competitive in the semiconductor industry for economic and national security reasons. These concerns also speak to the strength of the US industry: US SME firms are best-in-class and China wants to buy as much SME as possible from them.

The US government can and should limit these sales, but should be careful not to unduly harm US SME firms lest they choose to off-shore manufacturing to avoid controls they perceive as too burdensome.

Background: US Export Controls on SME and China

For background, quoting from an (excellent) CSET report on the subject:

Currently, the United States applies multiple types of semiconductor export controls on China. “List-based controls” is a term of art that refers to a list of specific technologies whose export is controlled. “End-use and end-user controls” refer to lists of prohibited end-uses for exported technologies and end-users that cannot receive exports. To export any controlled items, exporters must obtain export licenses—which can be denied by licensing officers.

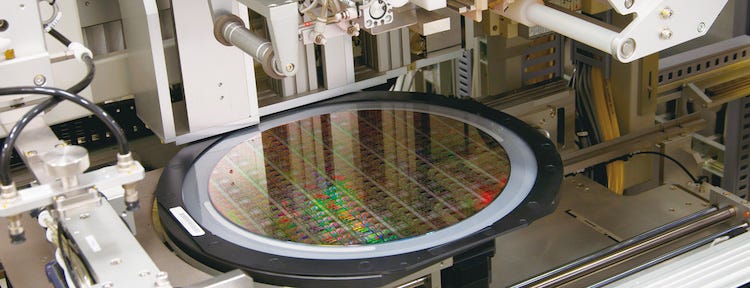

Controls on exports of US SME cover “some types of lithography, deposition, ion implanting, testing, and wafer handling tools, but not etching, process control, assembly, and wafer manufacturing tools.” Yet US licensing policy has been quite permissive until recently, allowing China to buy nearly any equipment it wanted from US firms.

The CSET report (see p. 21/22) has some shocking numbers: US exports of SME to China doubled between 2014-19, yet in 2018 only seven SME license applications were filed and all were approved. Translation: US SME firms sold hundreds (likely thousands) of pieces of SME to China during this time worth $billions, almost all of it did not require an export control license application, and even those sales that did require a license were nearly always granted approval, upon review.

The View from DC

The view from DC with regard to (w/r/t) export controls on SME has changed dramatically in the last three years (mainly due to FIRRMA/ECRA), and now views this permissive policy as a mistake. The temptation is to swing licensing policy hard in the opposite direction and start clamping down on sales of a broad swath of US-origin SME to a broad list of end users (Chinese customers) and end uses (applications such as supercomputing, surveillance etc). But there seems to be an emerging consensus that US controls on SME be limited and targeted.

Writ-large, the current view might be summarized as “given that the US government has decided its necessary to put controls on exports of SME to China, those controls should be limited (A) to select pieces of advanced equipment and (B) to select end-users/end-uses (C) in coordination with allied countries who are home to SME companies that could otherwise fill the void of US supply.”

This A/B/C view reflects several realities and challenges:

Point A: key technological chokepoints (sole-source suppliers) exist for extreme ultraviolet lithography tools, argon fluoride immersion photolithography tools, and a lot of metrology/inspection tools. Generally speaking, its possible to know which tools are used to make the best chips and which are used to make “the rest.” The industry would argue controls should only be applied to the former and they should be allowed to continue to sell the latter to any and all Chinese firms. However the decision to sell or not to sell some of this equipment is out of the hands of the US government: EUV tools, for example, are not made in the US (I’ll spare well-versed readers the rehash of Cymer, ASML, & FDPR debate for now).

Point B: US SME firms rely on sales to the Chinese market to fund the R&D needed to maintain their leading position in this industry. Loss of sales = loss of lead. There is a real risk that Applied Materials, KLA, and/or Lam Research off-shore some of their production to work around export controls they deem unduly onerous. KLA has already made comments to this effect. The fewer end-users (SMIC, HiSilicon) and end-uses (like surveillance equipment in Xinjiang using US chips) subject to new licensing requirements/export controls, the better in the eyes of US industry.

Point C: There is widespread foreign availability of nearly all SME, though a big difference exists between the best-in-class producers and the rest. This foreign availability means that, in the event that US companies like Applied Materials, KLA, and Lam Research were unilaterally prevented from selling to Chinese firms, companies in Taiwan, South Korea, Europe, and Japan could fill the void to some extent and would happily sell to China, absent pressure against doing so from their own governments.

The View from Government:

A GAO report from 2002 found that export controls on SME to China, even when multilateralized through The Wassenaar Arrangement, were ineffective because the US was the only country that voluntarily implemented them. A follow up report from 2008 found that focusing controls on end-users in China was also ineffective. The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) Assistant Secretary from 2010-17 echoes this conclusion in recent testimony. Additionally, in 2015 BIS determined: “foreign availability exists for anisotropic plasma dry etching equipment controlled for national security reasons,” particularly in China, and determined that it should lift controls. More recently, the National Security Commission on AI recommended multilateral export controls on SME.

The House GOP’s 2020 China Task Force report, while generally dismissive of the effectiveness of Wassenaar, recommends that the US engage allied partners (presumably Japan and the Netherlands) to apply controls on SME.

In Sum: it seems like subject matter experts in government recognize multilateral export controls on SME are the way to go. There is widespread foreign availability of most SME, so unilateral controls will do nothing more than harm domestic industry sales if they’re not coordinated with allied countries. BIS seems to be acting under this paradigm, focusing multilateral controls on SME-related goods solely at advanced node manufacturing in October 2020 (5nm in this case).

The View from Industry:

The US SME firms make several reoccurring points when asked about the effect of new export controls on their industry. Recent comments from Cadence Design Systems (an EDA tool vendor) are indicative:

Foreign Availability: There is widespread foreign availability of most SME, so unilateral controls that just prevent US firms from selling to China would simply push business to their competition. This loss of business would harm their R&D/innovation efforts.

Trade Diversion: The US SME industry has a global footprint and many firms have overseas subsidiaries. US SME firms may choose to re-orient their supply chains to increase overseas production to avoid a US government clamp-down on firm sales to China from the US branch of the company.

Competition: Unilateral controls on SME will incentivize China to subsidize production of indigenous SME companies, and incentivize Chinese firms to seek other suppliers/avoid purchasing from US suppliers as retribution. Both actions would hurt US SME competitiveness.

These points have been made by industry for several years. Lam Research, in comments on the 2018 BIS ANPRM on emerging technologies, said unilateral controls would have no impact on the ability of non-US companies to develop products comparable to theirs because there is current foreign availability for all of their technologies. They also included an exhaustive list of their competitors for every product type at the end of this document. Teradyne made the point even more explicitly, noting that:

“If Teradyne or any other US company were to have controls on the ability to share test development technology -- as a matter of law or foreign customer perception -- foreign companies have, or would easily have, the technical ability to step in and fill that the gap with foreign customers concerned that the US cannot be a reliable and quick supplier.”

In Sum: there is widespread foreign availability of most SME, so unilateral controls would hurt the US industry by denying them sales and allowing their competitors in other countries to fill those customers’s needs.

The View from Think Tank Land:

By my count, CNAS, CSET, and CSIS have all recommended multilateral controls on SME in one form or another.

Conclusion

Export controls on SME should only be applied on select equipment, against select firms, and in coordination with relevant allies. Broad export controls on categories of equipment, targeting an indiscriminate number of end users/end uses, and without allies, will hurt the US SME industry more than it hurts the target and may push US SME firms to offshore manufacturing.

A more interesting debate, which does not appear to be happening, is whether the export control system is the correct means to achieve the desired ends of the US government to hold back China’s technological ambitions. Financial sanctions (which can directly cut a target a firm off from all dollar-denominated transactions world wide) would achieve these goals more effectively, but there are considerable tradeoffs.

Note: these views are my own and informed solely by the information cited.